Can slimes think? Can something without a brain think?

What does it feel like to be a slime?

A slime splits in two. Which half is the original? Does it matter?

Slimes are ubiquitous across video and tabletop games media. From the oozes in Dungeons and Dragons to the slimes in the Dragon Quest series, these gelatinous monsters are often some of the first enemies encountered by adventurers in roleplaying games (other contenders for the title of most-frequent-early-game-battle include rats and bandits). Relatively unthreatening, slimes are perfect to cut one’s teeth against as a low-level would-be hero. In combat, they simply sort of bash their bodies into you, or reach out to whack you with a pseudopod, though some games feature more challenging, higher-level slimes capable of inflicting nasty status effects like poison.

The slime is a peculiar entity, though. Are they animals? They don’t really resemble any living thing known to us in the real world—the closest analogs would probably be molds (particularly the aptly named slime mold) or jellyfish and other sea creatures. Slimes also have, in many of their incarnations across games media, the ability to split into multiple individual slimes—a thing which can seem totally alien and strange to us but, in reality, isn’t wholly dissimilar to the asexual reproduction seen in certain flatworms, sea anemones, and corals. Whether or not they are animals isn’t necessarily the most interesting question, though. In the fictional fantasy worlds of games, they could simply be another category of living organism that exists in that world.

The better question is, do slimes think? For simplicity’s sake, let’s set aside for the moment the obvious fact that different games imagine slimes differently. Most slimes certainly seem to think: they will pick fights with adventurers, travel along paths with apparent purpose, and in several incarnations slimes are shown to eat and reproduce. Thinking about a slime’s capacity for thought presents several challenges, though. For one thing, they are often depicted as translucent such that one can see clear through the slime itself. Generally, they don’t have much (or any) visible internal anatomy to speak of. Certainly, peering into the inner workings of a slime reveals no obvious brain or nervous system.

So how, then, do we make sense of this creature that is clearly alive and seemingly acting as a rational being yet lacks anything resembling thought organs?

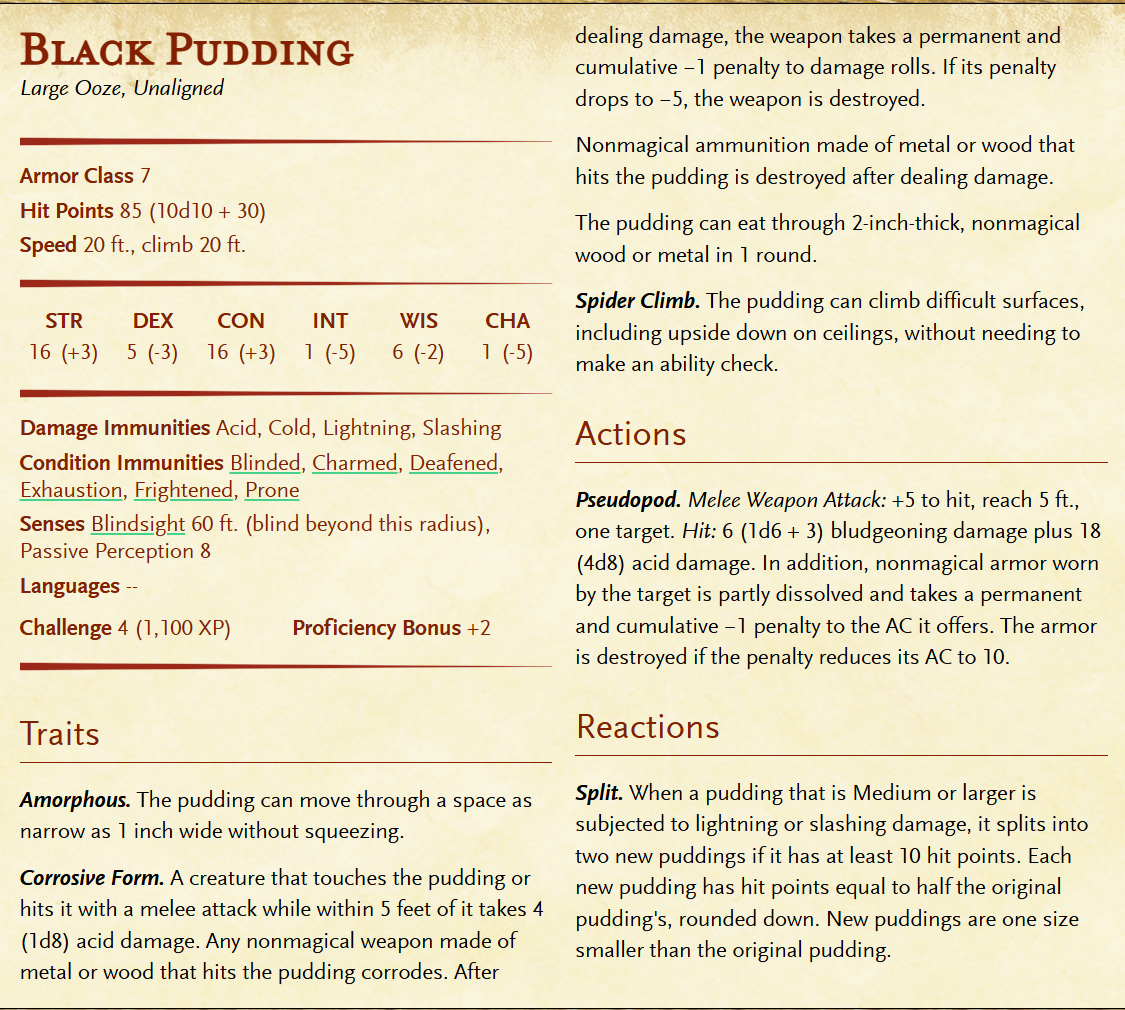

Let’s first return to the fact that each representation of slimes in games media will be somewhat different. In several Dragon Quest titles, slimes can talk, expressing opinions and desires, which marks them firmly as conscious beings. In stark contrast to this are the oozes in Dungeons and Dragons. According to the Monster Manual for the 5th edition of D&D, oozes act more on instinct rather than anything resembling rational decision making. Oozes in D&D are “drawn to movement and warmth” while avoiding light and extremes of temperature (240). The Monster Manual makes clear that oozes have no capacity for reason: “Most of the time, oozes have no sense of tactics or self-preservation” (240). Indeed, the statblocks for most types of oozes show an intelligence score of 1—the lowest possible ability score.

However, I don’t think oozes can be written off as entirely unthinking. After all, we do see wisdom scores of 6 for most oozes, including the black pudding, gelatinous cube, gray ooze, and ochre jelly. The Player’s Handbook tells us that wisdom is a measure of “awareness, intuition, and insight” (12). Now, 6 is a low score—but it’s not nothing. How can something completely lack consciousness yet possess the capacity for awareness, intuition, and insight? And the low intelligence scores of oozes does not detract from my argument—intelligence often refers to complex problem-solving and decision making while consciousness implies a subjective experience. We must conclude that oozes, in D&D, are conscious. Okay, okay, some would argue against this claim, stating that the production of consciousness is more complex than the sum of its parts and that awareness, intuition, or insight alone may not qualify as consciousness as it’s regularly understood. However, to this I would point out that there are several humanoid species in D&D which are clearly and obviously conscious in a way that few would dispute with similar wisdom scores. The kobold, for example, has a wisdom score of only 7. Besides, any player can create a humanoid character with a wisdom score of 6 or under. Therefore, I maintain my stance that the humble ooze has a similar capacity for awareness, intuition, and insight to some humanoids. This sort of speculation on the consciousness of fictional entities simply demonstrates that, well, consciousness is complex, and there may be gradients of consciousness and ways of being a conscious lifeform that we just don’t understand all that well.

So it doesn’t matter that we can see through the amorphous “bodies” of these slimes and see that there is no brain to be found—intelligence is there nonetheless. It just might not be the same kind of intelligence we’re used to thinking about.

While there must be hundreds if not thousands of games that feature slimes, we have briefly examined two of the most prominent examples in the form of Dragon Quest’s talking slimes and D&D’s (at least somewhat) wise oozes. Concluding that both exemplars are conscious to some degree, I turn now to the real-world possibility of intelligence appearing in unlikely places.

If the idea of a slime or ooze being intelligent—and here I do not use the D&D “ability score” definition of intelligence but rather intend to imply conscious intelligence—seems weird, consider the verdant world of plants. Serious botanists and thinkers like Stefano Mancuso and Alessandra Viola, authors of Brilliant Green: The Surprising History and Science of Plant Intelligence argue that while it may be a different type of intelligence from us, plants exhibit problem-solving and socialization. They build towards an argument favoring the protection of plant rights:

“For centuries, animals, too, were considered unthinking machines. It is only in the past several decades that we’ve begun to guarantee them rights, dignity, and respect: animals are not things anymore . . . Nothing like this exists for plants. The discussion of their rights is only beginning, but it can’t be put off any longer" (160).

Biologist and author Merlin Sheldrake takes a similar approach to thinking about fungal intelligence in his foundational book, Entangled Life: How Fungi Make Our Worlds, Change Our Minds, & Shape Our Futures:

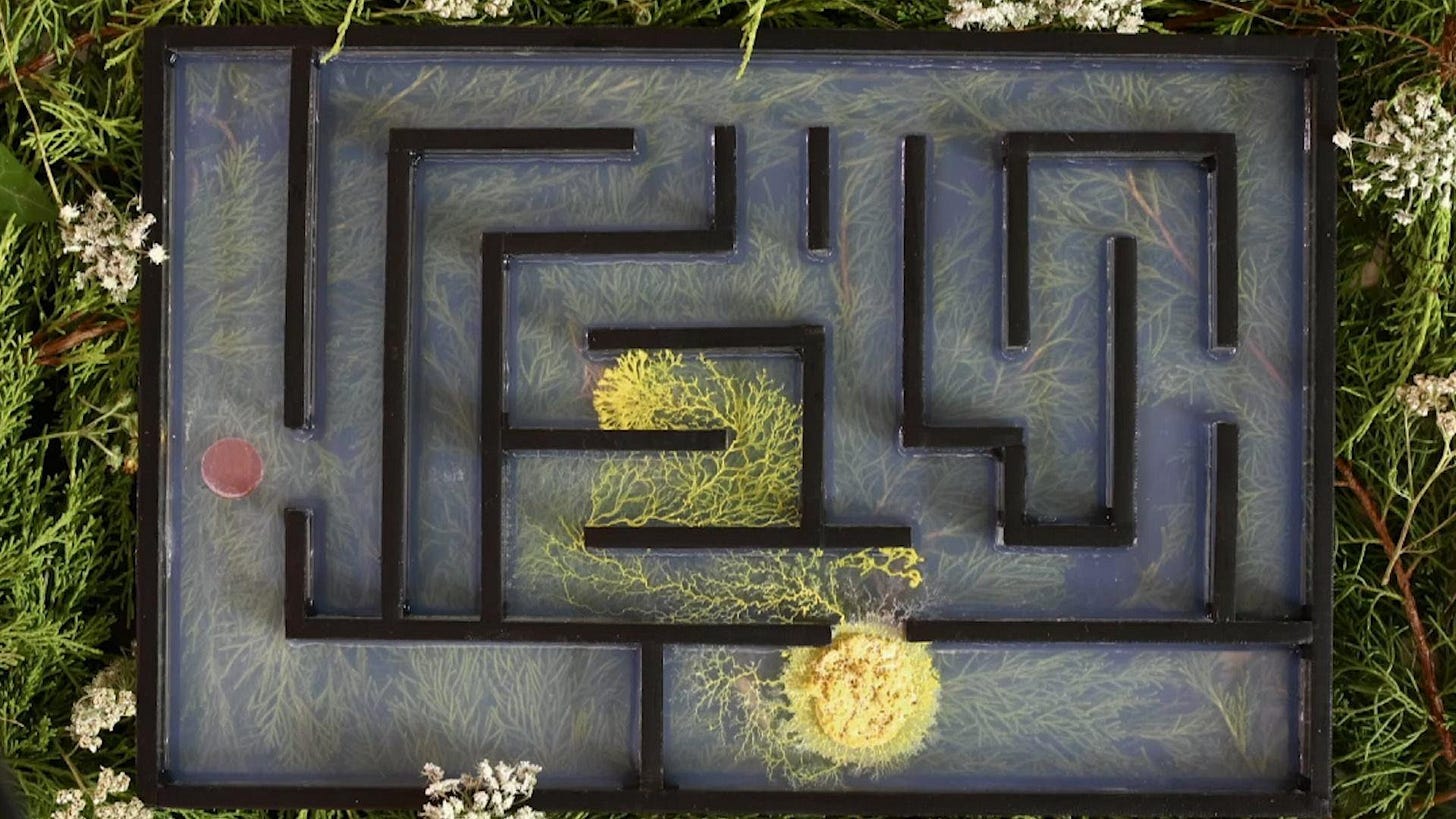

Whether one calls slime molds, fungi, and plants “intelligent” depends on one’s point of view. Classical scientific definitions of intelligence use humans as a yardstick by which all other species are measured. According to these anthropocentric definitions, humans are always at the top of the intelligence rankings, followed by animals that look like us (chimpanzees, bonobos, etc.), followed again by other “higher” animals, and onward and downward in a league table—a great chain of intelligence drawn up by the ancient Greeks, which persists one way or another to this day. Because these organisms don’t look like us or outwardly behave like us—or have brains—they have traditionally been allocated a position somewhere at the bottom of the scale. Too often, they are thought of as the inert backdrop to animal life. Yet many are capable of sophisticated behaviors that prompt us to think in new ways about what it means for organisms to “solve problems,” “communicate,” “make decisions,” “learn,” and “remember” (21-22).

As Sheldrake adeptly points out, we have an anthropocentric bias which causes us to privilege human intelligence over other types of intelligence. Sheldrake also highlights an important detail: the absence of a brain does not mean the absence of complex behaviors that we commonly associate with intelligence—even human intelligence.

So what does this mean for the slimes from our fantasy roleplaying games? Well, we have learned that scientists are increasingly taking nonhuman intelligence seriously, in some cases resulting in a restructuring of our preconceived notions of what qualifies as intelligence. In the real world, supporters of this stance argue that even brainless organisms can exhibit intelligence. And, as I’ve already discussed, slimes in some video games talk while others demonstrate wisdom (awareness, insight, and intuition) not dissimilar from some humanoids. So it doesn’t matter that we can see through the amorphous “bodies” of these slimes and see that there is no brain to be found—intelligence is there nonetheless. It just might not be the same kind of intelligence we’re used to thinking about.

One last point I’d like to end on—in many, many games featuring slimes, including Stardew Valley, Slay the Spire, Dungeons and Dragons, and countless others—slimes have a tendency to split into multiple smaller slimes. This can be seen in the statblock for the black pudding slime from D&D shown above. What does this splitting or fragmenting of the self into multiple selves mean for consciousness? Can consciousness be split between two or more organisms? What does it mean to decentralize consciousness?

These are questions I’ll have to leave to you, the reader, to answer. I’m not a philosopher of the mind, and these—questions about the nature and origin of consciousness—are some of the most complex questions that continue to elude us today. No one has shown exactly how the physical structure of the brain gives rise to consciousness. Perhaps panpsychism—the theory of the mind which postulates that consciousness is a fundamental feature of the universe akin to energy or charge and is not unique to human beings—could help us to understand what is happening when a singular slime splits into many individuals. That is, it’s possible that slimes possess a kind of proto-consciousness. Panpsychism not only says that consciousness isn’t unique to human beings, it also says that consciousness isn’t unique to living things. This means that consciousness isn’t dependent on the presence of a brain.

Slimes are fictional creatures, of course, but far from being a silly diversion, they can act as a cultural touchstone by which we can tackle the real and hard questions of our own universe. So the next time you see (or slay) a slime in a game, I encourage you to take just a moment to consider that this creature might just have an awareness hidden somewhere inside that gelatinous frame.

Further Reading

Brilliant Green: The Surprising History and Science of Plant Intelligence by Stefano Mancuso and Alessandra Viola.

Entangled Life: How Fungi Make Our Worlds, Change Our Minds, & Shape Our Futures by Merlin Sheldrake

Monster Manual. [Fifth edition]. Wizards Of The Coast, 2014.

Player’s Handbook. [Fifth edition]. Wizards Of The Coast, 2014.

Have thoughts on the consciousness of slimes? What did I get wrong? Join in the discussion—leave a comment below!

Looking at the concept of consciousness, wisdom, intelligence, at least through the D&D lens is really quite an interesting study for oozes, slimes, and puddings. You see quite a wide variety of stat blocks -- the Oblex Spawn (CR 1/4), as represented in Monsters of the Multiverse for example actually has an INT of 14 and WIS 11, indicating in theory at least higher levels of cognitive abilities. This is the lowest level of 'Oblex', which can progressively get stronger to adult and elder phases. What is fascinating here is that their abilities note how they absorb or feed on the minds and memories of the creatures they encounter, which begs the question then if their intelligence is essentially osmosed or if they possess any innate knowledge base of their own. The lore of these creatures does note however that they were the creation of the Mind Flayers, known for their intelligence and cunning. Rather than being a truly organic, 'natural' creature, they are more a genetically modified organism or science experiment.

On the other end, the 2024 edition of the PHB has a stat block for the menacingly titled 'Blob of Annihilation', a coagulation of cosmic entropy conjoined to the remains of dead gods". The entity can appear at random, oftentimes in connection with some major event. This creature, a Titan sized monster of CR 23 challenge, has an INT 10 and WIS 16 -- displaying average problem solving/logical abilities, and only moderately above levels of awareness and decision making powers. It is an interesting note -- a cosmic being, feasting on the mighty deities that forge and tear apart the cosmos, yet it seems to not reach their levels of intelligence.

Certainly, very interesting creatures, with questions of do they act on instinct or intelligence, by intent or by accident?

Pathfinder had a module, I think it was called "The Slithering," that was all about slimes. It didn't get into the idea of whether or not they are intelligent but it was fun to run it.

There is an anime' called something like: That Time I got Reincarnated as a Slime" that my son got me into. It's an odd little cartoon but I think it does say slimes are non-thinking and that is one reason it's super weird this guy got reincarnated as a slime and can still think.... I need to go watch that again, I didn't get very far.